Stand Your Ground

Distribution of Groundwater in Africa

Africa has an estimated total groundwater storage of 0.66 million km3, but this could be as high as 1.75 million km3. This is 100 times greater than annual renewable freshwater stores (MacDonald et al., 2012). Largest stores are found in Northern Africa – Egypt, Algeria, Sudan, and Libya. Groundwater plays a little role in agriculture with groundwater only used for crop irrigation on 1-2 million hectares in sub-Saharan Africa. This only contributes 1.5-3% to the livelihoods of the rural population. The respective figures for China and India are much higher – 30% and 50% (Giordano, 2006).

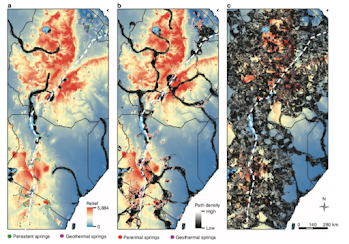

Aquifers are unevenly distributed in Africa relating to a ‘patchwork’ of climatological and physiographic configurations (Gaye and Tindimugaya, 2019). The availability of groundwater depends on geology and rainfall. It is because of these factors that the arrangement of groundwater storage differs across the continent with depth of aquifers contrasting significantly, shown in the map below.

Figure 1: Depth of Aquifers in Africa

Source:MacDonald et al., 2012

Potential of Groundwater Abstraction in Solving the Food Scarcity in Africa

Abstraction of groundwater is carried out through drilling boreholes. There is controversy over the potential of groundwater abstraction for irrigation due to yield rates. In general, a borehole must sustain a supply of at least >0.11s-1. However, the yield of boreholes required for crop irrigation is much higher. For example, intensive agriculture irrigation in the central plains of the US requires a borehole that can supply at least 501s-1(MacDonald et al., 2012).

Similarly, if aquifers have a depth greater than 50 m, this will make abstraction of groundwater by drilling boreholes with the cost increasing significantly as equipment required is more sophisticated (MacDonald et al., 2012).

Furthermore, the potential of groundwater abstraction in tackling food scarcity faces constraints depending on how educated natives are on management of pumps. As you can see from Figure 2, hand pumps are significantly complicated.

Figure 1: Hand pump for groundwater abstraction

Source: Afridev pump cross-section (RWSN, 2011)

Similarly, natives refrain from interfering and see management of Afridev pumps as the white man’s job and not given the tools to fix it. However, once the white men have drilled the boreholes and installed the pumps, they see their work here as done. But when the system breaks who will fix it? Not the Africans but not the white men either. So, how significant is the potential of groundwater abstraction through installing hand pumps if you are not to educate locals or come back to fix it? This ties in with the themes of colonialism and post-colonialism written about in my second blog post.

Let’s hear what the locals of the Masai tribe think

Utilization of groundwater supplies aims to increase agricultural potential which inevitably decreases food grain prices and works to reduce food scarcity in Africa. But this is not the case across the continent. The Kajiado district in Southern Kenya, is an ancient volcanic area with rivers running dry for half the year and home to the Masai tribe – a very independent tribe.

Boreholes are present every 25 kilometres with the Maasai forced to walk 2-3 kilometres when they have freshwater 2-3ft below them. Groundwater abstraction is underutilized due to a lack of hydraulic civilisations (Wittfogel, 1957). As discussed earlier, installation of hand pumps has modest potential since the Maasai tribe are uneducated in complex groundwater abstraction systems. Thus, the potential of groundwater abstraction in reducing food insecurity via hand pumps here is debateable.

Other means of technology are better placed to tackle food scarcity for the Maasai. The Maasai diet consists of meat or hide, and a type of bread made from cornflour and water which they grind together with their hands and a stone, as shown below. The Maasai have vocalized the advantages of installing a grinder to grind the bread and save the Maasai from walking into town. In their view installation of an automated grinder would be more beneficial in tackling food insecurity over installation of Afridev pumps due to the cultural traditions of the tribe and their preference for the traditional well, rope and bucket to abstract groundwater.

However, the underlining problem here is not the ill-educated members of the Maasai tribe but in fact the institutional mistakes which do not contextualise installation of groundwater abstraction pumps – as is the case with the Maasai tribe. ‘White men’ define there to be a problem concerning groundwater abstraction however this is false. It is only sensible that nomadic tribal traditions must be considered in defining problems of groundwater abstraction and similarly, the members of nomadic tribes defined when devising a solution.

Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, installation of groundwater abstraction pumps creates a situation of dependency and draws connotations of postcolonialism, as mentioned earlier. The situation of dependency that comes with installation of groundwater pumps would be refrained by the Maasai. This is because the Maasai tribe are a very independent, inseparable group who migrated to Kenya in 1852and retained their folklore. Hence, problems of groundwater abstraction are increasingly mistaken due to lack of contextualisation with some nomadic peoples able to live through periods of water stress as homosapiens once did (Cuthbert et al., 2017). A future blog post will draw upon this idea.

Source: JC Cuellar Photography

It is without doubt that the potential of groundwater in Africa is enormous. However, this post has raised questions over the effectiveness of installing hand pumps due to the high yield rate required for groundwater abstraction for agriculture, depths of aquifers, insufficient education of management of groundwater pumps, but more importantly the ignorance of institutions to neglect tribal traditions and assume it is a one-size-fits-all case across Africa.

Comments

Post a Comment